Jeff Turner - Indian Hater

The True Story Of A Pioneer Who Brought Revenge To The Indians For Killing His Family

“Whoever digs a pit will fall into it; if someone rolls a stone, it will roll back on them.” Proverbs 26:27

I learned recently that where I live, Weatherford, Texas, and surrounding areas, was once the “bleeding frontier” as S. C. Gwynne described it in his book Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History.

This book tells the story of the last Comanche chief, Quanah Parker, and the saga of the Texas settlers, including the Texas Rangers, and their clashes with the Indians, Comanches in particular, over a 40 year period, from the 1830’s through the 1870’s.

The rights to the story in this book has been in the hands of Warner Brothers to be made into a movie, but for some reason has sat in cold storage for years. The original screenwriter was Larry McMurtry (the iconic western author who wrote Lonesome Dove, Comanche Moon, and other westerns).

Here is S. C. Gwynne and Joe Rogan discussing it:

However, Empire of the Summer Moon’s rights have recently been optioned by Taylor Sheridan, who wrote Yellowstone, Sicario, Hell or High Water, Wind River (and a lot of other shows and movies), for a movie or series about Quanah Parker.

Incidentally, Taylor Sheridan lives down the road from me. He has a ranch called Bosque Ranch, which has an arena for performance horse events, including cutting horse events. My wife and I took the kids to see a cutting horse event there and had breakfast at their restaurant. Weatherford, Texas, is considered the cutting horse capital of the world.

Weatherford, and Parker County, and this area at large, was also the western frontier at one time, and the most dangerous place on earth if you were a settler.

According to G. A. Holland, who wrote History of Parker County and the Double Log Cabin in 1937:

It is estimated that from the first settlements in 1854 to the last raid in 1874, that within a radius of 100 miles-including Parker County, which was the worst sufferer-the Indians stole and destroyed six million dollar's worth of property, killed and scalped or carried away about 400 people into a captivity worse than death.

The Comanches had mastered riding and fighting, and dominated among the Plains Indians.

Weatherford is in Parker County, and Parker County was named after Isaac Parker, who was the uncle of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was Quanah Parker’s mother.

Cynthia Ann Parker’s family was raided by the Comanches and some other Indians in the 1830’s and she was captured and brought into the Comanche tribe when she was 9 years old. Years later she married a Comanche named Peta Nocona, and Nocona used to raid settler families in Parker County, including Weatherford (where Isaac Parker lived). My guess is that Peta Nocona was unaware that he was raiding the area founded by and still home to his wife’s uncle.

When I read Empire of the Summer Moon, I was quite frankly shocked at the sheer brutality on the western frontier. Some Indian tribes would torture their captives to death, either quickly or slowly depending on how much time they had to spare. The Tonkawa Indians were cannibals.

It’s important to give an accurate depiction of the fighting ability and brutality in plains warfare, in order to give a realistic backdrop behind the story of Jeff Turner.

To illustrate the brutality of the Comanches against the settlers, to take an example, I’ll focus on one story that happened in Parker County by Peta Nocona’s raiding party, just outside of Mineral Wells.

Texas Monthly gives a summary of the story of Comanche raiders attacking the Sherman family in western Parker County:

In late 1860 Nocona led a huge raid that set ablaze the settled frontier from Jacksboro to Weatherford. Afterward, a hard rain set in, and it was easy for the Texans to follow the Comanches’ horse tracks. A few weeks later, two companies of Rangers and a cavalry troop approached the Comanche camp on the Pease River. It was one of their favorite places; just north were the four sacred Medicine Mounds jutting up from the plains. A scout with the Texans was Charles Goodnight, the future trailblazer and Panhandle cattle baron. One of the young Ranger captains was Sul Ross, who would go on to become governor and the first president of Texas A&M University. Near the Pease, Goodnight found a Bible that had belonged to a young woman named Sherman. In a raid a few weeks before, the woman had been pregnant when the Indians surrounded her farm in the Palo Pinto country; they raped and scalped her and shot several arrows into her body. She lived long enough to have a stillborn baby, then died. For the Comanches, the stolen book was nothing more than tough packing material for their shields.

The woman’s name was Martha Sherman. She was approximately 9 months pregnant during the attack.

Accounts of this raid vary. One account claims that she was raped by at least 17 Comanches. Another account claims that she was raped by 5.

For whatever reason, they didn’t do a traditional scalping of the top of her head. They cut and hacked around her complete hairline, in an attempt to take her entire head of hair. But this was apparently proving difficult to do. In one account that I read, the Comanches threaded her hair into the tail of a horse, and had her drug behind the horse around the property, while two Comanches stood on her body, trying to dislodge her head of hair. Finally, one of the Comanches put his foot on her shoulder and yanked and her entire head of hair came off.

She kept retelling the story in her dying agony over four days to her husband and neighbors.

This raiding party had killed 23 people in two days around Parker County. Strangely, she kept talking about “that big red-haired Indian”, which might’ve been a white outlaw working with the Comanches.

I’m going to do a separate article and podcast about Martha Sherman, because she actually played a crucial role in what happened next with Cynthia Ann and her daughter Prairie Flower, Peta Nocona, and Quanah Parker, which had ironic and lasting consequences. In this piece, I’m also going to go more in-depth about the “red haired Indian”, because later scholarship may have uncovered his identity (this story in itself is really peculiar and interesting).

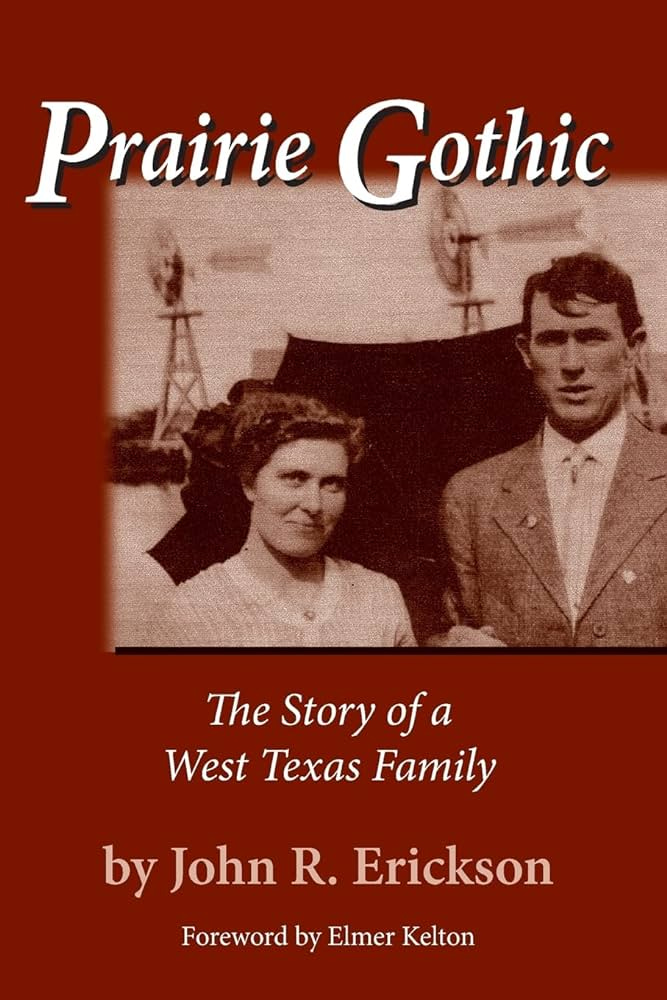

Martha Sherman was the great great grandmother of the author John R. Erickson, who wrote the Hank the Cowdog books. John R. Erickson describes what happened to his great great grandmother Martha Sherman in a book that he wrote called Prairie Gothic. The foreword of Prairie Gothic was written by my favorite Western author Elmer Kelton.

Jeff Turner - Indian Hater

The story of Jeff Turner - Indian Hater comes from the book The Adventures of Bigfoot Wallace, written by John C. Duval, published in 1870. John Duval and Bigfoot Wallace were fellow Texas Rangers, and they were both under the command of Jack Hays (who Hays County was named after).

By the way, the introduction of this book on Bigfoot Wallace, whose real name was William Wallace, claims that he is a descendent of William Wallace who led the Scots in the revolution against the English - the same William Wallace played by Mel Gibson in the movie Braveheart.

I looked up if William Wallace ever had any children, and there is no consensus. Some people say he did, and some say that he didn’t. Some people say we just don’t know. William “Bigfoot” Wallace’s ancestry was indeed Scottish.

I now can’t shake the idea that Bigfoot Wallace was the American version of William Wallace, the only difference being that he was fighting the Mexicans and Indians instead of the English.

Here is the relevant text from The Adventures of Bigfoot Wallace:

CHAPTER 17

“DID I ever tell you, asked Big-Foot, about a curious sort of character I fell in with at the "Zumwalt Settlement," on the La Vaca, a year or so after I came out to Texas? I have met with many a good honest hater in my time, but this fellow hated Indians with such a “vim" that he hadn't room left even for an appetite for his food.

But he had a good reason for it and if they had served me as they did him, I am afraid I should have taken to scalping Indians myself for a livelihood, instead of being satisfied with "upping" one now and then in a fair fight.

A party of eight of us had been out on an exploring expedition to the Nueces River, which was then almost unknown to the Americans, and the night we got back to the La Vaca we encamped on its western bank, and all went to sleep without the usual precaution of putting out a guard, thinking we were near enough to the settlements to be safe from the attacks of Indians.

I told the boys I thought we were running a great risk in not having any guard out, as I had already found that when you least expected to meet up with Indians, there they were sure to be; but the boys were all tired with their long day's ride, and said they didn't think there was any danger, and if there was they were willing to take the chances. So, after we had got some supper and staked our horses, we wrapped our blankets around us, and, as I have said before, were all soon fast asleep.

I was the first one to rouse up, about daylight the next morning, and, looking in the direction we had staked our horses, I discovered that they were all gone. I got up quietly, without waking any of the boys, and went out to reconnoitre the “sign." I had gone but a little ways on the prairie when I picked up an arrow, and a few yards farther on, I came across one of our horses lying dead on the grass, with a dozen "dogwood switches" sticking in various parts of his body.

This satisfied me at once that "Mr. John" had paid us a sociable visit during the night, and, with the exception of the one they had killed (he was an unruly beast), had carried off all our stock when they left. I went back to camp and stirred up the boys, and gave them the pleasing information that we were ten miles from "wood and water" and "flat afoot."

But there was no use in crying over the matter, so we held a "council of war" as to what was the best to be done under the circumstances; that is, flat afoot, with all our guns, saddles, bridles, and other equipment on hand, and ten miles to the nearest settlement.

At length, it was decided that each man should shoulder his own "plunder,"or leave it behind, as he preferred, and that we should take a "bee-line" to the "Zumwalt Settlement" above the river, borrow horses if we could, follow the Indians, and endeavor to get back from them those they had stolen from us. So we took a hasty snack, and, each man shouldering his pack, we put out on a "dog-trot" for the settlement.

It was a pretty fatiguing tramp, hampered as we were with our guns and rigging, but we made it in good time. Fortunately for us, a man had just come into the settlement, from the Rio Grande, with a large "caballado," (drove of horses), and when we made known our situation to him, he told us to go into the corral and select any of the horses we wanted.

They were only about half broke, and it took us fully an hour to catch, bridle, and saddle them, and fifteen minutes more to get on their backs. I was more lucky than most of the boys, for I only got two kicks and a bite before I mounted mine. When all was ready, we put spurs to our steeds and galloped back to our encampment of the night previous, where our horses had been stolen, and took the Indian trail, which was plainly visible in the rank grass that grew at that day along the bottoms of the river.

Several men belonging to the settlement had volunteered to accompany us, so that our number (rank, but not file, for we were all colonels, majors or captains, except one chap, who was a judge) amounted to thirteen men, well armed and mounted. As long as the Indians kept to the valley we had no trouble in following the trail, and pushed on as rapidly as we could. When we had travelled perhaps eight or ten miles, I had to halt and dismount for the purpose of fixing my girth, which by some means had become unfastened.

While I was engaged at this, I heard the tramp of a horse's hoofs behind me, and looking back the way we had come, I saw a man riding up rapidly on our trail. When he got up to where I was he reined in his horse, evidently intending to wait for me, and I had a chance of observing as curious a looking "specimen" as I ever saw before in any country.

He was a tall, spare-built chap, dressed in a buckskin hunting-shirt and leggings, with a coonskin cap on; a long, old-fashioned flint-and-steel Kentucky rifle on his shoulder, and a tomahawk and scalping knife stuck in his belt. His hair was matted together, and hung around his neck in great uncombed "swabs," and his eyes peered out from among it as bright as a couple of mesquite coals.

I have seen all sorts of eyes, of panthers, wolves, catamounts, leopards, and Mexican lions, but I never saw eyes that glittered, and flashed, and danced about like those in that man's head. He was mounted on a raw-boned, vicious looking horse, with an exceedingly heavy mane and tail; but notwithstanding his looks, any one could see, with half an eye, that he had a great deal of "let out" in him on a pinch.

As soon as I had patched up my girth, I mounted my horse again, and rode along sociably with this curious specimen for a mile or so, without a word passing between us; but I got tired of this, and, although I felt a little "skittish" of this strange-looking animal, I at length made a "pass at him," and inquired if he was a stranger in these parts.

"Not exactly," said he. "I have been about here 'off and on' for the last three years, and I know every trail and 'water-hole' from this to the Rio Grande, especially those that are used much by the Indians going and coming.

"And ain't you afraid," I asked, "to travel about so much in this country alone?" He grinned a sort of sickly smile, and his fingers clutched the handle of his tomahawk, and his eyes danced a perfect jig in his head.

"No," he answered; "the Indians are more afraid of me than I am of them. If they knew I was waylaying a particular trail, they would go forty miles out of their way to give me a wide berth; but the trouble is, they never know where to find me. And, besides," he continued, "the best horse this side of the Brazos can't come alongside of 'Pepper-Pod' when I want him to work in the lead."

As he said this, he touched up Pepper-Pod smartly with his spurs, who gave a vicious plunge, and started off like a "shot out of a shovel." But he soon reined him up, and we rodé on together again in silence for some time. Finally, I said to him "Man of family, I suppose?" Gracious! If a ten-pound howitzer had been fired off just then at my ear, I couldn't have been more astonished than I was at this chap's actions. He turned pale, and his lips quivered, and he fumbled with the handle of his butcher-knife, and his eyes looked like two lightning-bugs in a dark night.

He didn't answer me for a while, but at length he said "No, I have no family now. Ten years ago, I had a wife and three little boys, but the Indians murdered them all in cold blood. I have got a few of them for it, though," he went on, "and if I am spared, I’ll get a few more before I die;" and as he said this he clicked the triggers of his rifle, and pushed the butcher-knife up and down in its scabbard, his eyes danced in his head worse than ever, and he gave Pepper-Pod another dig in the ribs, who reared and plunged in a way that would have emptied any one out of the saddle, except a number-one rider.

After a while, he and Pepper-Pod both quieted down a little, and he said to me: “You mustn't think strange of me. I always get in these 'flurries' when I think of the way the Indians murdered my poor wife and my little boys. But I wíll tell you my story.”

CHAPTER 18

“TEN years ago," said the strange-looking man, "I was as happy a man as any in the world; but now I am miserable except when I am waylaying or shooting or scalping an Indian. It's the only comfort I have now." I had a small farm in Kentucky, not far from the mouth of the Beech Fork, and though we had no money, we lived happily and comfortably, and had nothing to fear when we laid down at night.

But, in an unlucky hour for us, a stranger stopped at my house one day on his way to Texas, and told me about the rich lands, the abundance of game, and the many fortunes that had been made in this new country. From that time I grew restless and discontented, and determined, as soon as possible, that I would seek my fortune in that 'promised land.'

"The next fall I had a chance to sell my little farm for a good price, and we moved off to Texas, and, after wandering around for some time, finally settled on the banks of a beautiful little stream that runs into the Guadalupe River. My wife had left Kentucky very unwillingly, but the lovely spot we had chosen for our Home, the rich lands and beautiful country around, and the mildness of the climate, at length reconciled her to the move we had made.

"One lovely morning in May, when the sun was shining brightly, and the birds were singing in every tree, I took my rifle and went out for a stroll in the woods. When I left the house, my wife was at work in our little garden, singing as gayly as one of the birds, and my three little boys were laughing, and shouting, and trundling their hoops around the yard. That was the last time I ever saw any of them alive. I had gone perhaps a mile, entirely unsuspicious of all danger, when I heard a dozen guns go off in the direction of my house.

The idea flashed across my mind in a moment that the Indians were murdering my family, and I flew toward the house with the speed of a frightened deer. From the direction in which I approached it, it was hid from view by a thick grove of elm-trees that grew in front of the house. I hurried through this, and rushed into the open door of the house, and the first thing I saw was the dead body of my poor wife, lying pale and bloody upon the floor, and the lifeless form of my youngest boy clasped tightly in her arms. She had evidently tried to defend him to the last. The two older boys lay dead near by, scalped, and covered with blood from their wounds.

The Indians, who had left the house for some purpose, at that instant returned, and, before they knew I was there, I shot one through the heart with my rifle, and, drawing my butcher-knife, rushed upon the balance like a tiger. There were at least a dozen of the savages, but if there had been a thousand of them it would have made no difference to me, for I was desperate and reckless of my life, and thought only of avenging the cruel and cowardly murder of my poor wife and children.

"I have but a faint recollection of what happened after this. I remember hearing yells of fright and astonishment the Indians gave as I rushed upon them, and that I cut to pieces several of them with my butcher-knife before they could escape through the door—and then all was a blank, and I knew nothing more. I suppose some of those outside fired upon me, and gave me the wounds that rendered me senseless, but I gave them such a scare it was evident they never entered the house again, as otherwise, you know, they would have taken my scalp, and carried off the dead Indians.

Some time during the day, one of my neighbors happened to pass by the house, and noticing the unusual silence that prevailed, and seeing no one moving about, he suspected something was wrong, and came in, and the dreadful sight I have described to you met his eyes.

He told me afterward he found me lying on the floor, across the body of an Indian, still grasping his throat with one hand, and with the other the handle of my knife, which was buried to the hilt in his breast. Near by lay the bodies of three other Indians, gashed and hacked with the terrible wounds I had given them with my butcher-knife. My kind neighbor, observing some signs of life left in me, took me to his house, dressed my wounds, and did all that he could for me.

For many days I lay at the point of death, and they thought I would never get well; but gradually my wounds healed up and my strength returned; although for a long time afterward I wasn't exactly right here (tapping his forehead) and even now I am more like a crazy man than anything else, when I have to go a long time without 'lifting' the scalp from the head of an Indian; for then I always see, especially when I lay down at night, the bloody corpses of my wife and poor little boys."

"I hope, my friend," I replied, for I didn't like the way his eyes danced in his head, and the careless manner he had of cocking his gun and slinging it around—"I hope you have had your regular rations lately, and that you don't feel disposed to take a white man's scalp when an Indian's can't be had handily."

The fellow actually chuckled when I said this, the first time I had heard anything like a laugh from him, "Oh, no," he said; "I have been tolerably well supplied of late, and could get along pretty comfortably without a scalp for a week or so yet. I have forty-six of them hanging up now in my camp on the Chicolite, but I shan't be satisfied unless I can get a cool hundred of them before I die; and I'll have 'em, too, just as sure's my name is Jeff Turner."

Again his eyes glared out of his bushy locks, and his fingers again began to fumble about his knife handle, in a way, that, if I had had a drop of Indian blood in my veins, would have made me feel exceedingly uneasy. At last, to change the subject, I asked him which way he was traveling, though, of course, I knew very well he was going along with us. "Any way," he replied, "that these. Indians go. I'd just as soon go in one direction as another. I always travel on the freshest Indian trail I come across. You and your company may get tired and quit this trail without overtaking the Indians, but I shall stick to it until I get a scalp or two to take back with me to my camp on the Chicolite."

By this time we had come up with our companions, and all rode on in silence. At length we came to a hard, rocky piece of ground, where the Indians had scattered, and we lost the trail altogether, for not the least sign was visible to our eyes. At that time, you see, none of us had had much experience in the way of trailing and fighting Indians, except Jeff Turner, the "Indian-hater." We soon discovered that he knew more about following a trail than all of us put together, and from this time on, we let him take the lead, and followed him everywhere he went.

Sometimes, where the ground was very hard and rocky, and the Indians had scattered, he would hesitate for a little while as to the course to pursue, but in a moment or so he was all right again, and off at such a rate that we were compelled to travel at a full trot to keep up with him. About half an hour before sundown, he came to a halt, and when we had all gathered around him, he told us to keep a sharp lookout, and make no noise, as the Indians were close by; and, in fact, we had scarcely travelled three hundred yards farther when we saw their blanket tents on the edge of some post-oak timber, about a quarter of a mile to our right. We put spurs to our horses, and in a few moments we were among them.

CHAPTER 19

The Indians didn't see us until we were within fifty yards of their encampment, but still they had time to seize their guns, and bows and arrows, and give us a volley as we charged up; but luckily no damage was done except slightly wounding one of our horses.

We dismounted at once and commenced pouring a deadly fire into them from our rifles. Just as I sprang from the saddle to the ground, a big Indian stepped from behind a post-oak tree and drew an arrow upon me that looked to me as long as a barber's pole. I jumped behind another tree as spry as a city clerk in a dry-goods store when a parcel of women come around shopping, and not much time had I to spare at that, for the arrow grazed my head so closely that it took off a strip of bark from it about the width of one of my fingers.

I leveled my rifle and drew a bead upon him as he started to run, but his arrow had rather unsettled my nerves, and I missed him fairly. The fight was kept up pretty hotly on both sides for fifteen or twenty minutes, when the Indians soured on it, and retreated into a thick chaparral, leaving seven of their warriors dead upon the ground. I noticed my friend Jeff several times during the fight, and each time he was engaged in "lifting the hair" from the head of an Indian that either he or some one else had shot down.

They say that "practice makes perfect," and it was astonishing to see how quickly Jeff would take off an Indian scalp and load his rifle in readiness for another. One slash with his butcher-knife and a sudden jerk, and the bloody scalp was soon dangling from his belt. At the same time, he never seemed to be in a hurry, but was as cool and deliberate about everything he did as a carpenter when he is working by the day and not by the job.

When the Indians began to retreat, one of them jumped on one of our horses, (which they had tied hard and fast to post-oaks near their camp), forgetting in his hurry, to unfasten the rope, and round and round the tree he went, until he wound himself up to the body, when just at that instant Jeff plugged him with a half-ounce bullet, and had his scalp off before he had done kicking. After the Indians had retreated to the chaparral, a little incident occurred that shows the pluck of these red rascals when they have been "brought to bay."

We were standing all huddled up together, loading our rifles, for we did not know but that the Indians had retreated on purpose to throw us off our guard, when all at once we were startled by a keen yell and the firing of a gun, and at the same instant a tall chap by the name of B, who had come with us from the settlements, dropped his rifle, and, clapping his hands to his face, cried out: "Boys, I am a dead man!" I looked around to see from whence the shot had come, and discovered an Indian lying on the grass, about thirty yards off, with his gun in his hand, slowly sinking back upon the earth again, from which he had partially raised himself by a dying effort to take a last pop at the enemies of his race.

I had seen this Indian fall during the fight, and supposed, of course, that he was dead—as he was, in fact, an instant after he gave the yell and fired his gun; for I went up immediately to where he lay, and found that he was dead as a door nail, with his gun still tightly clasped in his hands; and yet at the time he fired at B he had no less than seven rifle-balls through various parts of his body, for the wounds were plainly to be seen, as he had nothing on to speak of, except his powder-horn and shot pouch.

Our "Indian-hater," Jeff, came up to him about the same time I did, and lifted the hair from his head before you could say "Jack Robinson," and strung it on his belt to keep company with three other scalps that were already dangling from it. The scalps seemed to ease the mind of Jeff considerably, as he told me they would, and he got quite sociable with the boys after the fight, and once actually laughed outright, when one of them told a funny story about shooting at a stump three times for an Indian before he discovered his mistake ; but either the unusual sound of his own laugh frightened him, or else he had used up all his stock on hand, for I never saw him crack a smile afterward.

As it turned out, B was worse scared than hurt, for the Indian's bullet had only grazed his head, but, striking the black-jack tree near which he was standing, it had thrown the rough bark violently into his eyes, the pain from which led him to suppose he was a dead man.

The Indians had killed a fat buck, and when we pounced upon them they had the choice pieces spitted before the fire, and after the fight we found them "done to a turn." We hadn't eaten a bite all day, and seized upon the venison as the lawful spoils of war, and made a hearty supper upon it, together with some hard-tack which we had brought along with us in our haversacks. While I was eating supper, I couldn't help feeling a little sorry for the poor creatures who had cooked it only an hour before, and who were now lying around us cold and stiff on the damp grass of the prairie, so soon to be devoured by vultures and cayotes.

However, this thought didn't take away my appetite, or, if it did, a side of roasted ribs and about five pounds of solid meat disappeared along with it. As soon as we had finished supper, we changed our saddles from the horses we had ridden to those the Indians had stolen from us (which had been resting for some time), and mounting, we took the trail back towards the settlement, where we arrived about sun-up the next morning, making seventy-five miles we had travelled in part of a day and night, without ever getting off our horses except for a few moments, when we fought the Indians.

Jeff, the Indian-hater, left us here for his camp on the Chicolite, and I never saw him again. I was told when I was at the settlement several years after this, that he staid around there for a good while, occasionally coming into the settlement for his supplies of ammunition, etc., and always bringing with him four or five scalps. At length, he went off and never returned, and it is supposed that the Indians finally caught him napping. At any rate, that was the last that was ever seen or heard of Jeff Turner, the "Indian-hater."

Jeff was a lone-wolf vigilante, fighting the most dangerous tribe in the most hostile place in the world.

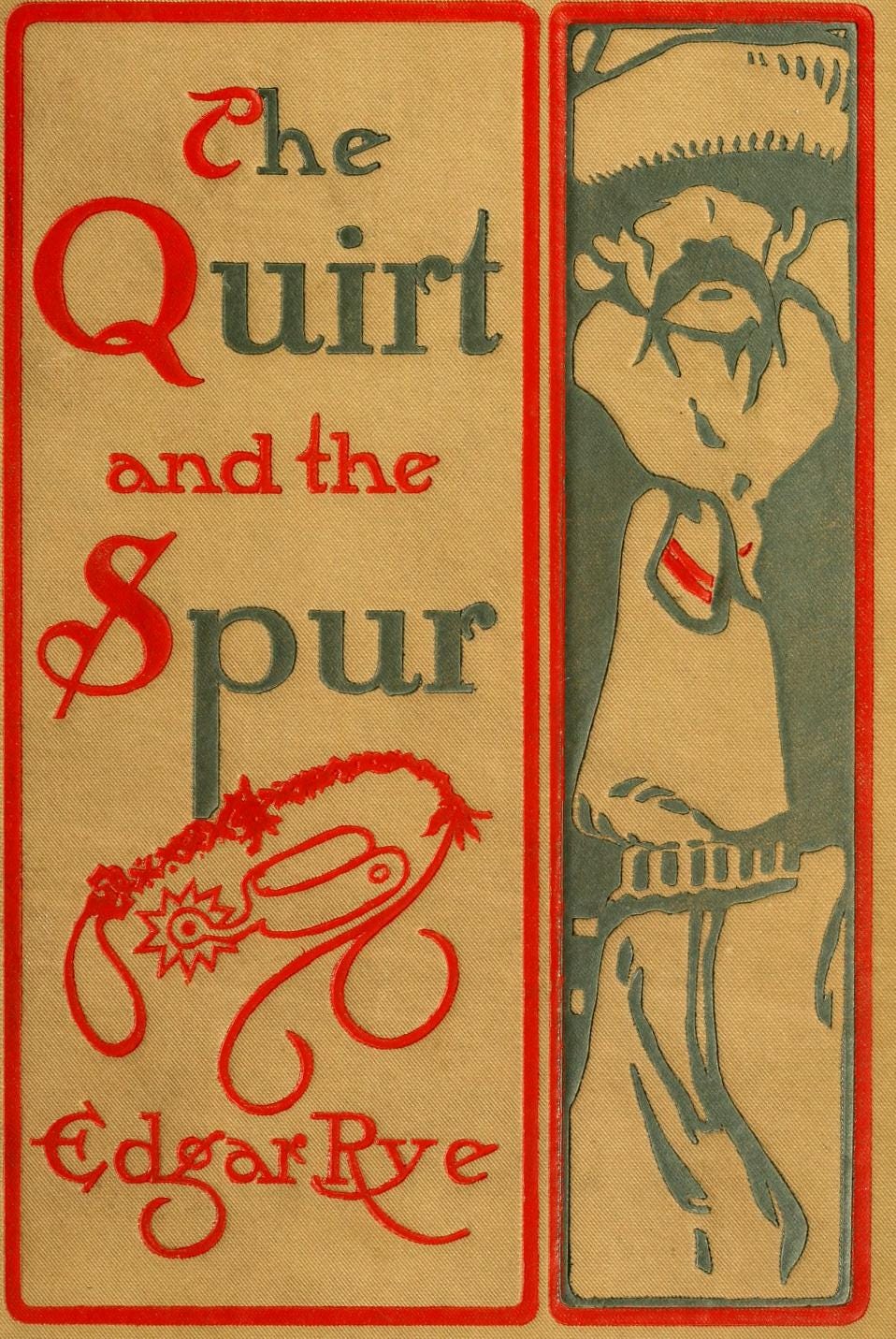

There are two very different accounts that describe what happened to Jeff Turner after his encounter with Bigfoot Wallace, and how he died. One account comes from The Quirt and the Spur, a book published in 1909, written by Edgar Rye.

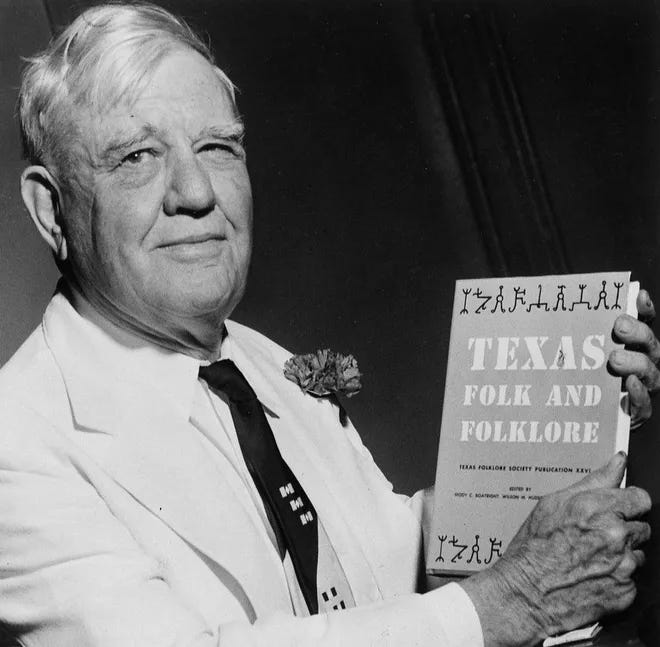

The American folklorist and western writer J. Frank Dobie discusses the account that The Quirt and the Spur gives of Jeff Turner’s death, and he also tells a very different story that he got second-hand from Bigfoot Wallace - which details a horrific death at the hands of Indians, presumably the Comanches. Both accounts can be read in J. Frank Dobie’s article called Between the Comanche and the Rattlesnake, which I quote from here.

“NOT MUCH IS DOWN in writing about Jeff Turner the Indian Hater, but in frontier households his name was once a familiar. Many white people considered him a monomaniac, which he was; Indians looked upon him as a devil, which he was also. The only description of him that I have found is in John C. Duval's Adventures of Bigfoot Wallace, wherein old Bigfoot does most of the talking. Jeff Turner, he said, “was as curious a looking specimen as I ever saw in any country.

He was tall, spare-built, dressed in buckskin shirt and leggins, and wore a coonskin cap. His hair was matted together and hung around his neck and over his eyes in great uncombed swabs, and his eyes peered out from them as bright as a couple of mesquite coals.

I have seen all sorts of eyes - panther, wolf, catamount, leopard - but I never saw eyes that glittered and flashed and danced like those in that man's head. He rode a raw-boned, vicious-looking horse named Pepper-Pod, and carried a long, old-fashioned flint-and-steel Kentucky rifle on his shoulder or across his saddle.”

Turner had come to Texas from Kentucky and settled on the Guadalupe River with his wife and three small boys. One day he came in from a hunt to find all four dead and Indians scalping them. He got four Indians and after that lived for the one purpose of killing and scalping more Indians.

He could be counted on to join any expedition against them, but habitually hunted and waylaid alone. His type was rare, but he had precedents. "Mad Anne" Bailey of Virginia (1747-1825) was perhaps the most noted; after her husband was killed by Indians she lived only to avenge. Charles Goodnight used to tell of coming one rainy night upon a solitary frontiersman in his cabin curing a freshly-taken Indian scalp over the fire; in retribution for a daughter killed by Indians while she was suckling a baby, he cherished a collection of these well-preserved trophies.

Any dedicated hater is a warped abnormality. The haters represented by Jeff Turner are not to be classed among those murderous scalpers for bounty led by Santiago (James) Kirker and John Glanton, who in Chihuahua and Sonora collected not only on Apache scalps but on equally dark hair from innocent Mexican citizens.

Jeff Turner's career of single-minded vengeance began some time before Texas became a state. He told Bigfoot Wallace that whenever he had to go a long spell without lifting hair he got to feeling "peculiar."

During the preceding ten years, he said, he had hung up forty-six scalps in his camp, but wouldn't die "satisfied until he had a cool hundred." How many scalps Jeff Turner got before he died, I have no idea. How he died is in the realm of tradition.

In a book entitled The Quirt and the Spur (Chicago, 1909) by Edgar Rye, the ending of Jeff Turner the Indian Hater is bound to rattlesnakes. [Edgar] Rye was a frontier newspaper editor; he could do nearly everything but stick to facts.

Not that he was averse to facts, but if they were not handy or suitable to the dramatic, he frequently used something else. His book, which centers around Fort Griffin during buffalo days, contains real characters and realistic facts along with fabrications and a lot of talk in quotation marks that is absurdly false to life. An oddity in the book named Smoky tells what follows, here much abbreviated.

About the time the Civil War closed, Smoky, ranging alone in the Fort Phantom Hill country, fell in with Jeff Turner.

As usual, Turner was hunting scalps, and plenty of scalps were around. While they were trying to save a fool camped out in the open with his wagon and family on the Clear Fork of the Brazos, a band of Comanches turned the tables on them. The two frontiersmen killed two and got away in darkness and took up what proved to be a boxed canyon, the Indians hot behind. They couldn't turn back down the canyon; they couldn't climb out of it, and now, the sure-of-victory Indians yelling on their trail like bloodhounds, they came to the head of it.

Feeling in the darkness, Smoky discovered a hole, about as big around as a barrel, in the blockading wall overhead. They pulled up into it and found themselves in what Jeff Turner called a "kind of underground prairie." The ceiling to it was so low that they had to crawl to move about; the floor was "damp and slimy." After they had crawled back a way, they heard in the dense darkness the blood-curdling rattle of a rattlesnake.

Anybody who in darkness has ever heard that rattling almost at his feet will agree that it curdles the blood. They halted motionless. Smoky knew that Jeff Turner had a box of Mexican wax matches, which burn like miniature tapers. He whispered to Turner to strike one. Turner lit it. "Not more than ten feet away a wriggling mass of writhing, twisting rattlesnakes" began to untangle themselves and crawl about in all directions. Most of them seemed to be diamondbacks.

The men, resting at the moment on their knees, remained as if paralyzed, not moving even to strike another match. Darkness could be no deeper; tensity could be no tenser. Finally, after what seemed an immeasurable time of immobile kneeling, Turner's cramped muscles must have made him relax.

He moved to shift his weight. There was a whir, and then he said, "Smoky, I have lifted my last scalp." In a little while he began to twist about and to rave. Presently he grabbed Smoky by the arm and said in a hoarse, thick voice, "Look! There's a hole in the ground right in front of me. It's the skylight to hell, and I wonder why the devil left it uncovered."

Then in extravagancies that would have satisfied any exhorter holding sinners over brimstone furnaces, he described his own advance into the torture of heat and the power of hellish beings. He died about the time a dim light told Smoky which way to get back to the mouth of the cave. Before this, he knew not when, the rattlesnakes had vanished. The Comanches also had left the canyon. Smoky buried what was left of Jeff Turner the Indian Hater within sight of the ghostly chimneys that still mark the site of Fort Phantom Hill.”

The historic Fort Phantom Hill is located in Abilene, Texas. And you can still see the chimneys.

J. Frank Dobie continues:

“One December night in 1932 while I was in a hotel in El Paso, a vigorous knocking made me jump to my feet. When I opened the door, the frame was filled with man, over six feet of him, all in powerful proportions, wearing an enormous Western hat not at all disproportionate to the wearer.

The man was Frank Collinson, now dead. In the early seventies he had come from England to Texas, where he took with gusto to mustanging, buffalo-hunting, ranching, and other forms of open range life. He had a background of reading and the perspective of civilization, and in his latter years he wrote considerably for Western magazines. That night before he sat down, in a big chair in my hotel room, he began talking. After a while he asked if I had known Bigfoot Wallace. I hadn't.

He had, on the Medina River, west of San Antonio, where Bigfoot batched alone. "Did you ever hear of Jeff Turner the Indian Hater?" Frank Collinson asked. "Yes," I replied, "I have read about him in Duval's book on Bigfoot Wallace." "Does the book tell what became of Jeff Turner?" "No, and I have often wondered." "Well, Bigfoot told me. He said that Turner kept on hounding Indians, picking off one when he could and saving his scalp, until one night they found him out in the brush asleep by himself.

He was too valuable to kill right there. They took him to their camp, where the wife of a chief was soon to give birth to a baby - a boy they hoped. They spread-eagled Jeff Turner on the ground and sat this chief's wife down beside him. Then the chief cut out Turner's heart and while it was still palpitating gave it to her to eat hot and raw. The belief was that Turner's bravery would thus be transferred to the unborn child."

When I heard this story, I understood why Duval, who belonged to the Victorian Age and who wrote his books originally for publication in a magazine for boys and girls, did not tell what became of Jeff Turner. But maybe that's just a story; again, maybe it's fact.

If you remember, Bigfoot Wallace said “At length, he went off and never returned, and it is supposed that the Indians finally caught him napping” about Jeff Turner. And his friend Frank Collinson said to J. Frank Dobie "Well, Bigfoot told me. He said that Turner kept on hounding Indians, picking off one when he could and saving his scalp, until one night they found him out in the brush asleep by himself.”

I think we can say with at least some confidence that Jeff Turner - Indian Hater, fought his heart out.